The current boom in AI has been sold to businesses as a great productivity improvement opportunity, at least by the AI vendors and the industry of consultants being paid to help with AI projects. There has been rapid adoption of the technology, with OpenAI’s ChatGPT having 800 million active weekly users, and 78% of companies using AI to a greater or lesser degree. However, the software industry has a history of over-promising and under-delivering – do you remember non-fungible tokens (NFTs)? So, what is the evidence for **AI productivity** in real-life usage rather than PowerPoint charts?

Many companies have been cutting jobs or freezing hiring based on the anticipated productivity boom that AI will bring. Yet so far, there is **mixed evidence** about the effect of AI on the job market. A 30th September Financial Times article quoted a US study by Yale University, which said “Overall, our metrics indicate that the broader labor market has not experienced a discernible disruption since ChatGPT’s release 33 months ago“. A Goldman Sachs report in August 2025 reckoned that unemployment may increase 0.5% due to AI but “we remain sceptical that AI will lead to large employment reductions over the next decade“.

A 2025 survey of a thousand executives by Orgvue found that 55% of companies that had laid off staff, hoping for savings via AI, now **regretted it**. 38% admitted that they don’t understand what impact AI will have on their business. A remarkable 72% of Fortune 500 companies disclosed AI as a material risk on their 10-K forms in their annual filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission in 2025. The top concerns cited were reputational risk (38% of companies), cybersecurity risk (20%), followed by regulatory or legal risks.

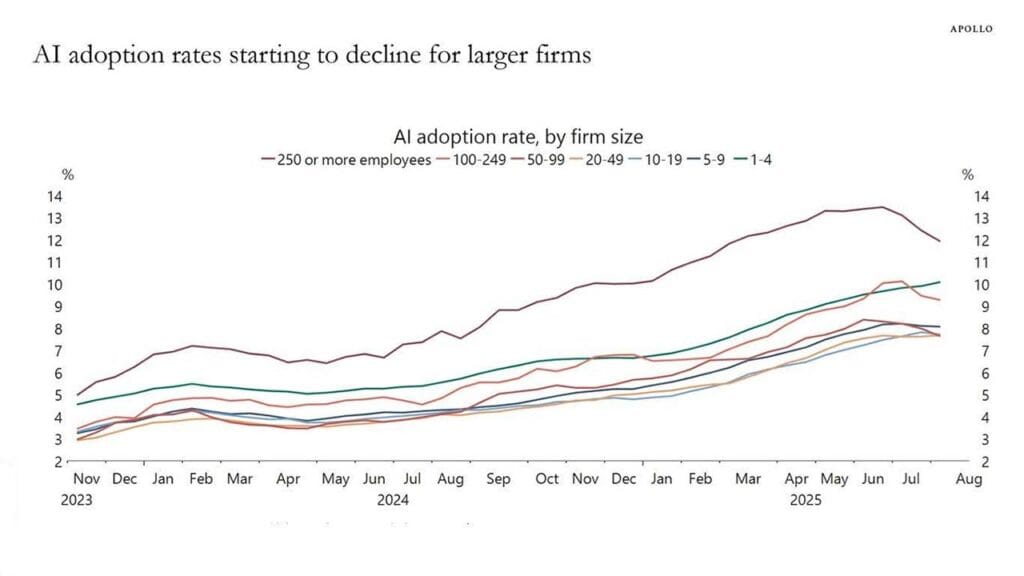

Intriguingly, US census data, based on a biweekly survey of 1.2 million firms, showed that **AI adoption was actually declining** in September 2025.

Source: US Census Bureau, quoted in Apollo Academy research report

Source: US Census Bureau, quoted in Apollo Academy research report

A number of recent studies and reports have cast doubt on whether many of the perceived productivity gains from AI are showing up in reality. A widely reported MIT study of hundreds of AI projects found that **95% of them failed to deliver any return on investment** whatsoever. An October 2025 EY report surveying almost a thousand companies found that **99% of them had suffered financial losses** due to AI risks, with $4.4 million per company being a “conservative estimate”. This means that just the 975 companies surveyed alone had suffered $4.3 billion of financial losses due to AI-associated risks.

These studies are not alone. A new word entered the AI lexicon recently: **“workslop”**. This is when AI-generated material is sent to workers that looks plausible but either lacks substance or contains errors. A recent Stanford University study found that **40% of the US desk workers** surveyed had received AI “workslop” in the last month, taking an average of two hours to resolve each incident. A September 2025 Harvard Business Review report said that AI-generated “workslop” is destroying productivity. CNN reported it as creating an “invisible tax” on businesses. Publisher Wiley surveyed scientists and found that they were **significantly less trusting of AI** in 2025 than they were in the same survey of 2024.

Technology journalist Cory Doctorow said recently that “AI is the asbestos we are shovelling into the walls of our society, and our descendants will be digging it out for generations”. Currently, over half of all internet content is AI-generated, and a May 2025 study reckoned that 74% of new webpages contained AI content. Given that, it is to be hoped that Mr Doctorow’s prediction turns out to be wrong. However, the increasing amount of AI-generated material on the internet creates other issues: LLMs that are trained on AI-generated material do badly, often ending up in “model collapse”. This phenomenon may be one reason why, despite three years of AI model development since the launch of ChatGPT-3, the performance of LLMs since then is, on some measures, actually worse than it was at the time of the launch, though there have clearly been strides forward in other areas, such as the quality of image and video generation.

One of the areas where generative AI has seemed to show the highest adoption rate has been software engineering. Large language models (LLMs) can carry out multiple tasks in software engineering, from writing code to generating test cases, producing systems documentation and helping in debugging. Yet it is interesting that the trust in AI code by practitioners is low and is worsening. The massive annual Stack Overflow study of developers came out at the end of July 2025, its fifteenth edition, with 49,000 participants across 177 countries. 84% of respondents used AI in software development, but **46% did not trust its output**, a large increase from 31% in the same survey last year. Prashanth Chandrasekar, CEO of Stack Overflow, said: “The growing lack of trust in AI tools stood out to us as the key data point in this year’s survey”. 75% of people in the survey did not trust AI answers, and 62% had security concerns about the generated code. These results align with another very large developer survey, the earlier annual Dora survey. In this, 39% of respondents have “little or no trust” in AI-generated code.

This compares with another recent large survey by KPMG, a general survey rather than aimed at developers, that found that amongst the 48,000 respondents, just 8.5% always trust AI results, while **54% are wary** of trusting AI. A separate survey showed that **16% of employees pretend to use AI at work** to please their boss, with 22% feeling pressured to use AI where it was not appropriate. Three years on from the release of ChatGPT, we are starting to see a significant number of surveys that are measuring the effectiveness of AI in practice. There seems to be a growing disparity between the level of trust in AI among executives and the people actually using it on a day-to-day basis. Much of this, I believe, comes down to companies trying to fit a square LLM peg into a round work-shaped hole. There are undoubtedly good use cases for LLMs, and even more for the more general ecosystem of AI, such as machine learning and reinforcement learning. However, the evidence is mounting that LLMs have been oversold as a silver bullet solution to general productivity. I will leave you with another Cory Doctorow quote: “AI cannot do your job, but an AI salesman can 100 per cent convince your boss to fire you and replace you with an AI that can’t do your job.”